Infinite divisibility (probability)

The concepts of infinite divisibility and the decomposition of distributions arise in probability and statistics in relation to seeking families of probability distributions that might be a natural choice in certain applications, in the same way that the normal distribution is. The distributions sought correspond to random variables which are equivalent to the sums of a number of independent and identically distributed random variables, where the number of such variables can be set to any pre-specified number.

The term infinitely divisible characteristic function is used for the characteristic function of any infinitely divisible distribution.[1]

The concept of infinite divisibility of probability distributions was introduced in 1929 by Bruno de Finetti. These distributions play a very important role in probability theory in the context of limit theorems.[1]

Contents |

Definition

In probability theory, to say that a probability distribution F on the real line is infinitely divisible means that, for every positive integer n, there exist n independent identically distributed random variables Xn1, ..., Xnn whose sum Sn = Xn1 + … + Xnn has the distribution F.

Examples

The Poisson distribution, the negative binomial distribution, the Gamma distribution and the degenerate distribution are examples of infinitely divisible distributions; as are the normal distribution, Cauchy distribution and all other members of the stable distribution family. The uniform distribution and the binomial distribution are not infinitely divisible.[2] The Student's t-distribution is infinitely divisible, while the distribution of the reciprocal of a random variable having a Student's t-distribution, is not.[3]

Limit theorem

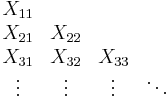

Infinitely divisible distributions appear in a broad generalization of the central limit theorem: the limit as n → +∞ of the sum Sn = Xn1 + … Xnn of independent uniformly asymptotically negligible (u.a.n.) random variables within a triangular array

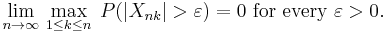

approaches — in the weak sense — an infinitely divisible distribution. The uniformly asymptotically negligible (u.a.n.) condition is given by

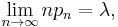

Thus, for example, if the uniform asymptotic negligibility (u.a.n.) condition is satisfied via an appropriate scaling of identically distributed random variables with finite variance, the weak convergence is to the normal distribution in the classical version of the central limit theorem. More generally, if the u.a.n. condition is satisfied via a scaling of identically distributed random variables (with not necessarily finite second moment), then the weak convergence is to a stable distribution. On the other hand, for a triangular array of independent (unscaled) Bernoulli random variables where the u.a.n. condition is satisfied through

the weak convergence of the sum is to the Poisson distribution with mean λ as shown by the familiar proof of the law of small numbers.

Lévy process

Every infinitely divisible probability distribution corresponds in a natural way to a Lévy process. A Lévy process is a stochastic process { Lt : t ≥ 0 } with stationary independent increments, where stationary means that for s < t, the probability distribution of Lt − Ls depends only on t − s and where independent increments means that that difference Lt − Ls is independent of the corresponding difference on any interval not overlapping with [s, t], and similarly for any finite number of mutually non-overlapping intervals.

If { Lt : t ≥ 0 } is a Lévy process then, for any t ≥ 0, the random variable Lt will be infinitely divisible: for any n, we can choose (Xn0, Xn1, …, Xnn) = (Lt/n − L0, L2t/n − Lt/n, …, Lt − L(n-1)t/n). Similarly, Lt − Ls is infinitely divisible for any s < t.

On the other hand, if F is an infinitely divisible distribution, we can construct a Lévy process { Lt : t ≥ 0 } from it. For any interval [s, t] where t − s > 0 equals a rational number p/q, we can define Lt − Ls to have the same distribution as Xq1 + Xq2 + … + Xqp. Irrational values of t − s > 0 are handled via a continuity argument.

See also

References

- ^ a b Lukacs, E. (1970) Characteristic Functions, Griffin , London. p. 107

- ^ Sato, Ken-iti (1999). Lévy Processes and Infinitely Divisible Distributions. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0521553025.

- ^ Johnson, N.L., Kotz, S., Balakrishnan, N. (1995) Continuous Univariate Distributions, Volume 2, 2nd Edition. Wiley, ISBN 0-471-58494-0 (Chapter 28, page 368)

- Domínguez-Molina, J.A.; Rocha-Arteaga, A. (2007) "On the Infinite Divisibility of some Skewed Symmetric Distributions". Statistics and Probability Letters, 77 (6), 644–648 doi:10.1016/j.spl.2006.09.014

- Steutel, F. W. (1979), "Infinite Divisibility in Theory and Practice" (with discussion), Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 6, 57–64.

- Steutel, F. W. and Van Harn, K. (2003), Infinite Divisibility of Probability Distributions on the Real Line (Marcel Dekker).